We conduct research to understand the implications and effects of community involvement and dialogue in promoting health, planning health services, and quality improvement of existing services.

Our work spans six key research themes

- Health experiences and practices

- Community participation and co-production

- Transitions to adulthood

- Evaluation and methodology

- Ethics and epistemology

- Digital lives

Find out more about our work on community participation, patient engagement, and dialogues for health - including plain-English summaries

Meet the DEPTH team at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

We conduct research to understand the implications and effects of community involvement and dialogue in promoting health, planning health services, and quality improvement of existing services.

- Health experiences and practices

-

Using interviews and other innovative ways to elicit voices and experiences, we explore how social lives and health practices are intertwined. Much of our work involves dialogues about sexual and reproductive health and practice in diverse communities around the world. Examples include the sixteen18 project which explored young peopleŌĆÖs sexual practices in the UK, and our Ghana project where we interviewed women about their fertility practices. Our work shows how introducing and promoting more honest and critical dialogues about sexual and reproductive health improves understanding of complex dynamics in relationships and hidden practices.

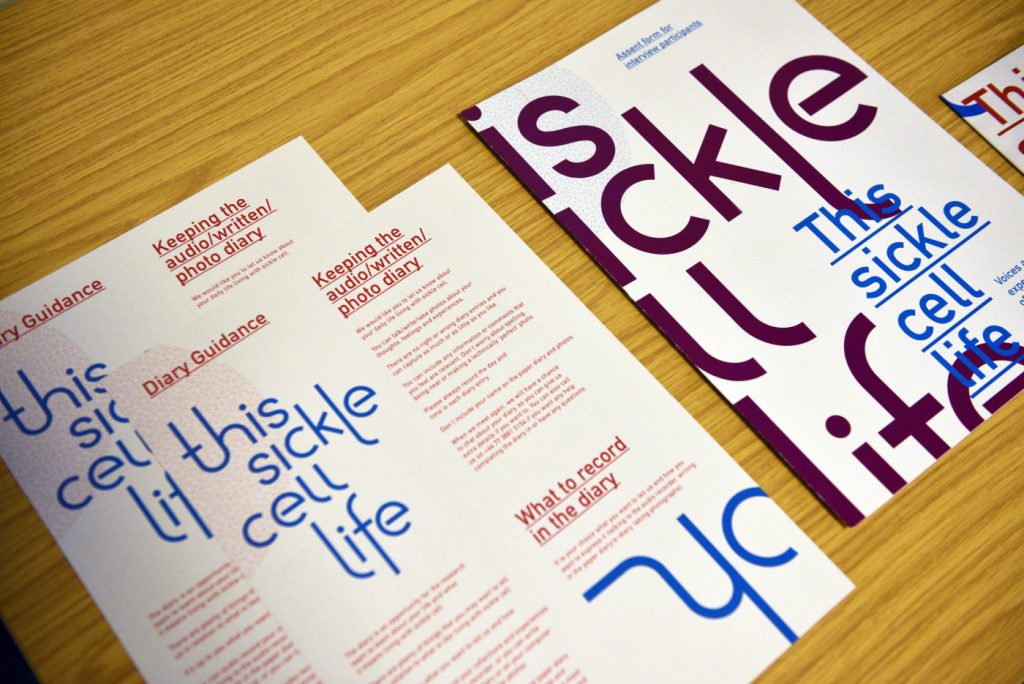

When it comes to health experiences, voice is key. Our recent project 'This Sickle Cell Life', a sociological study of young people's experiences of paediatric to adult healthcare transitions, highlighted the importance of listening to the voices of young people with sickle cell. In this project and across our work, we examine the implications of dialogue for understanding experiences and developing more inclusive forms of knowledge. We also explore which voices are heard in conversations about health and which are left out.

- Community participation and co-production

-

Our work on community participation and citizenship has involved long term ethnographic explorations of public and patient involvement and engagement in research and quality improvement in the UK National Health Service. This research has helped us build theory around community participation, engagement, and empowerment, their effects, and the implications for citizenship in health. This work also addresses practical aspects of how to make participation successful such as how to create effective and inclusive spaces for participation, and how to orientate organisational culture so it helps rather than hinders participation.

Our international activities include work with the WHO (World Health Organisation) on guidelines on community participation to promote maternal and newborn health, as well as informing the ŌĆścommunity engagementŌĆÖ action area of the Global Strategy for WomenŌĆÖs, ChildrenŌĆÖs and AdolescentsŌĆÖ Health.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the crucial importance of dialogue, evidence, and participation for health. Dialogue and co-production are essential for effective pandemic response. Global health guidelines already emphasise the importance of community participation, but in a pandemic, it is more important than ever to involve communities in planning and response. Marginalised communities and individuals are disproportionately harmed by COVID-19 and those communities are best-placed to know what is most needed to help them. Co-production ŌĆō collaborative work between researchers, clinicians, patients and the public ŌĆō can improve health, and help reduce inequalities by addressing diverse needs and helping ensure that actions do not cause harm. Co-produced healthcare responses to COVID-19 are more likely to address specific needs, identify gaps in policy, and find solutions by working together.

- Transitions to adulthood

-

Our work has examined young peopleŌĆÖs transitions to adulthood, ways that sexuality, sexual practice and contraception are bound up in life experiences and identity, and health and wellbeing of adolescents and young people.

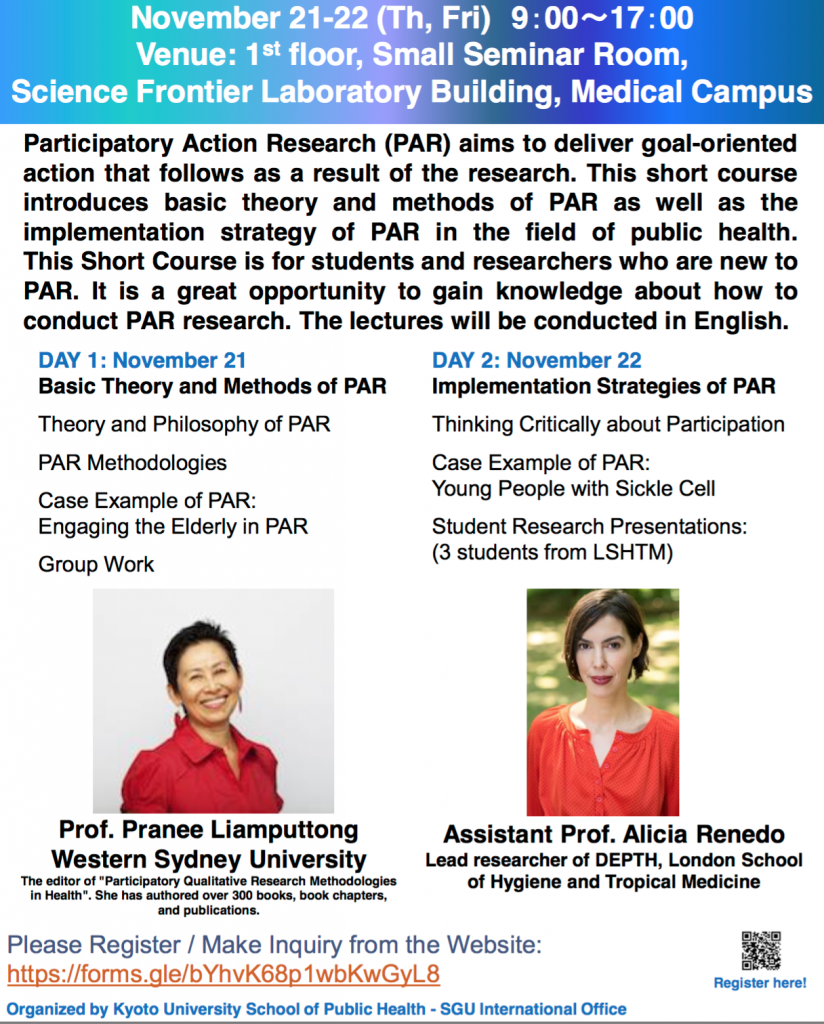

In This Sickle Cell Life, we took a sociological approach to look beyond the clinical realm into other areas relevant to transitions to adulthood such as education and social relationships. Working in collaboration with patient representatives, social scientists, clinicians and quality improvement experts, the project facilitated dialogue about how transitions into adult healthcare can be improved, including how to improve health services for people with sickle cell.

- Evaluation and methodology

-

Developing evaluation methodology, particularly for complex social interventions, is a core interest for the team. Our recent work has included developing ways to evaluate a partner violence prevention intervention for young people that was part of a comprehensive sexuality education programme, how to , and ways to evaluate SRHR interventions for marginalised populations in complex and challenging environments in our lead research role for the ACCESS consortium.

- Ethics and epistemology

-

Accurate science communication is crucial if people are to make informed decisions about their health. We work with the World Health Organization to ensure that global guidelines are based on the best interpretation of the scientific evidence. We also work with other groups such as COMPare in Oxford to investigate potentially unethical practices in trial reporting. We have debunked and also revealed how effectiveness claims about a version of the rhythm method (the Standard Days Method) are being used to heavily promote it in low-income settings.

Conducting and communicating our research in an ethical way is key to promoting valuable dialogue with a range of people. By acknowledging the gaps in the way that researchers listen to participants, we can think of ways to improve on taking our lead from the participant. We want to amplify the voices that are less heard.

- Digital lives

-

We are increasingly investigating digital life as a key mediator of dialogue, personhood and community. We are particularly interested in how dialogues are promoted and restrained in increasingly digital lives, and the interrelationships between digital lives and health.

Our work includes advising government and providing commentary and analysis on effects of pornography on young people, and theoretical explorations of the use of mobile phone locative media apps such as .

We have also examined public views and experiences of using electronic health records for research.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the crucial importance of dialogue, evidence, and participation for health. DEPTH is committed to inclusive, participatory action in the COVID-19 response.

Dialogue and co-production are essential for effective pandemic response

Global health guidelines already emphasise the importance of community participation, but in a pandemic, it is more important than ever to involve communities in planning and response. Marginalised communities and individuals are disproportionately harmed by COVID-19 and those communities are best-placed to know what is most needed to help them. ŌĆō collaborative work between researchers, clinicians, patients and the public ŌĆō can improve health, and help reduce inequalities by addressing diverse needs and helping ensure that actions do not cause harm. Co-produced healthcare responses to COVID-19 are more likely to address specific needs, identify gaps in policy, and find solutions by working together.

Pandemic responses have largely involved governments telling communities what to do, seemingly with little community input. We are concerned that the few existing spaces for community participation in the UK such as in the NHS are being shut down and overall, citizen participation is noticeable by its absence.

Communities clearly want to help: in the UK half a million people volunteered to help the NHS pandemic response, and highly localised mutual aid groups are springing up all over the world in which citizens help one another with simple tasks and check on wellbeing during lockdowns. The most vulnerable and ignored groups can help identify solutions: they know what knowledge and rumours are circulating; they can provide insight into stigma and structural barriers; and they are well placed to work with others from their communities to devise collective responses.

Working with communities means collaborating to create tailored ways to meet the full needs of our diverse populations. Community-led responses are also more likely to be acceptable, feasible, and sustainable.

The above is expanded upon in a recent commentary we published in the Lancet, which you can read for free .

Co-production in the COVID-19 pandemic is extremely challenging, but our past work shows how important it is to involve communities. Find out more about our research on community participation and patient and public involvement in healthcare:

- Addressing sexual and reproductive health and rights in crisis

-

In times of crisis, sexual and reproductive health and rights are often not prioritised. With all areas of the health system strained by the emergency response to COVID-19, there is a risk that resources for sexual and reproductive health services may be reduced or diverted, particularly in low-resource settings, compromising or harming sexual and reproductive health and rights ŌĆō particularly for the most marginalised.

As part of the ACCESS consortium, DEPTH proposes to research how best to work with communities to co-produce pandemic response to SRHR needs for the most marginalised people living in complex and challenging environments including humanitarian settings. You can read more about our proposed work here.

- Ensuring the pandemic response includes the most marginalised

-

DEPTH co-produced research into the impacts of sickle cell disease, This Sickle Cell Life, has already demonstrated how chronic health conditions shape young peopleŌĆÖs lives, and, crucially, the negative consequences of failing to involve patients as experts in their own condition. Our collaborative research with patient and carer experts identified key challenges which are likely to be exacerbated with COVID-19, including failure of non-specialist hospital staff to understand or meet the specific needs of people with sickle cell, leading to poor care. Failing to involve patients in healthcare responses to the pandemic risks amplifying existing disadvantages and inequities for the most vulnerable. You can read more about This Sickle Cell Life here.

- Build back better, more sustainable, more inclusive healthcare

-

Our work has shown how important it is to . We must include communities throughout the response, and when we rebuild, draw on those same engagement networks and community groups to ensure that damaged health systems are more efficient, more inclusive, and more robust to shocks and crises.

DEPTH work has been incorporated into the Community Engagement action area of the , and DEPTH researchers participate in the WHO-convened Community of Practice on Social Accountability. We research community participation in healthcare, including in times of crisis, to understand how to co-create an effective, sustainable response.

- Developing community involvement and co-production even in lockdown

-

DEPTH will work with ACCESS consortium partners to investigate how community involvement is maintained in crisis and whether the most marginalised are being included. We will investigate ways to strengthen existing networks and set up new ones in the most complex and challenging environments to ensure nobody is left behind.

- Learn what works, when, how, and for whom

-

We will advance global understanding of how to improve sexual and in crises, attending to the social context of interventions, and intended and unintended impacts on equity and rights. We will explore co-production, and impact of complex interventions in dynamic contexts, drawing both on the methodological expertise within DEPTH and that of our colleagues in the Centre for Evaluation, and on our work on the nature of , , and .

Routes: new ways to talk about covid for better health. Focus on Gypsy Roma and Traveller communities, and migrant workers in precarious jobs

Overview

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities and migrant workers often experience worse health than the general population, with existing inequalities exacerbated further by the Covid-19 pandemic. Understanding health experiences within these communities and co-designing solutions is vital to improve health equity and health services.

The project involves participatory research with Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, and with migrant workers in precarious jobs, using our ŌĆśDEPTHŌĆÖ approach, to identify and address barriers to good health. We work with policymakers, healthcare staff, and communities to generate rigorous evidence and to co-produce research and solutions that are tailored, meaningful, feasible and effective.

Our approach involves community members as co-researchers to ensure that we ask the right questions, contextualise the responses properly, and find solutions together. We are exploring real life experiences relevant to Covid-19 risk, prevention and response, and co-producing solutions via dialogues about the findings. By co-producing the research, we will understand specifics of health experiences and needs, and how best to address them. While we are focusing on Covid-19 prevention, we anticipate that our findings will also be transferable to other areas of health.

Outcomes

By using our DEPTH approach, particularly as it relates to community participation in Covid-19 health responses we will generate rigorous evidence, and co-produce recommendations that are evidence-based, address real community concerns, and are acceptable and feasible.

We aim to promote dialogue and generate knowledge, with Gypsy,ŌĆ»Roma, Traveller, and migrant worker communities, to understand: ŌĆ»

- experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic;

- experiences and views of public health responses to Covid-19;

- when and why people do or do not engage with different elements of Covid-19 prevention, taking account of broader issues with engagement with health services; ŌĆ»

- how people's living and working conditions affectŌĆ»their ability to protect themselves from Covid-19 and to engageŌĆ»with health initiatives, focusing on test and trace;

- Understand the broader social context affecting peopleŌĆÖs lives and how this affects health and use of health services.

Using evidence from the project we will then engage in dialogues with communities and other key stakeholders to co-produce recommendations relevant to the public health response to Covid-19.

Outputs

Project outputs included regular ŌĆśthree key findingsŌĆÖ policy briefs delivered to the policy teams at regular intervals during the project. There are five publications, all free to download:

- K├╝hlbrandt, Charlotte; McGowan, Catherine R; Stuart, Rachel; Grenfell, Pippa; Miles, Sam; Renedo, Alicia; Marston, Cicely; (2023) Vaccine, 41 (26). pp. 3891-3897. ISSN 0264-410X DOI:

- Miles, Sam; Renedo, Alicia; K├╝hlbrandt, Charlotte; McGowan, Catherine; Stuart, Rachel; Grenfell, Pippa; Marston, Cicely; (2023) Sociology of health & illness. pp. 1-18. ISSN 0141-9889 DOI:

- Renedo, Alicia; Stuart, Rachel; K├╝hlbrandt, Charlotte; Grenfell, Pippa; McGowan, Catherine R; Miles, Sam; Farrow, Serena; Marston, Cicely; (2023) SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 3. 100280-. ISSN 2667-3215 DOI:

- Stuart, Rachel; Grenfell, Pippa; Renedo, Alicia; McGowan Catherine R; K├╝hlbrandt, Charlotte; Miles, Sam; Marston, Cicely. . British Society of Criminology Online Journal Vol 22 pp.24-38

- Marston, Cicely; McGowan, Catherine; Stuart, Rachel; Kuhlbrandt, Charlotte; Miles, Sam; Grenfell, Pippa; Dix, Laura; Renedo, Alicia; (2022) Project Report. DEPTH Project, London.

This project was funded by NHIR Public Health Policy Research Unit. Read more about the project, and other projects.

ACCESS: Improving sexual and reproductive health and rights in complex and challenging environments

In 2019 LSHTM researchers began an ambitious piece of work funded by UK Aid: the ACCESS consortium, led by the International Planned Parenthood Federation, aimed to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in complex and challenging environments including humanitarian settings in Nepal, Uganda, Mozambique and Lebanon.

Contraception and safe abortion care services, HIV/STI prevention, treatment and care, and comprehensive sexuality education are often poor or unavailable to marginalised groups in many parts of the world. Multiple complex and interconnected barriers impede universal access to good SRHR. Access to rights-based services, such as contraception and comprehensive sexuality education, is often compromised or denied, and barriers to achieving SRHR, including sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), may disproportionately affect marginalised groups.

Funded by (initially via the UK Department for International Development, later the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office) Consortium (2019-21) created innovative solutions to ensure that marginalised people including young people, disabled people and refugees are not left behind.

The ACCESS consortium was led by the (IPPF) and was selected within the UK Aid Connect programme. partnered with IPPF, , the , the and , bringing a wide range of expertise to generate sustainable, scalable, rights-based approaches to deliver comprehensive SRHR to all. The research was led by the (DEPTH) research group in collaboration with academic staff from across the institution, under the leadership of Professor Cicely Marston, principal investigator for LSHTM, Director of the DEPTH research group, and research director for the consortium. The co-creation phase (April 2019-March 2020) was completed, but the main, implementation phase of the consortium work was delayed by the pandemic and began in October 2020.

LSHTMŌĆÖs role within the consortium was to lead on research, creating a strong evidence-base for what works to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for the most marginalised groups living in complex and challenging environments, including humanitarian settings.

We planned to do this through three interconnected workstreams:

- Formative research into lives, needs, contexts and services: we planned to conduct research to understand the lives and needs of marginalised people and how we might improve their sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). This research would have informed interventions and advance knowledge.

- Evaluations of ACCESS consortium programme components: we were planning to evaluate the extent to which ACCESS mini-projects improve Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR).

- An evaluation of the ACCESS participatory approach as a whole (ŌĆśPractising, understanding and measuring participationŌĆÖ): we aimed to try to understand how participation and co-production work in practice to improve SRHR (including understanding and measuring participation and its effects across programme activities) and generate transferable insights to improve implementation of inclusive and successful participatory practice in other settings.

Policy barriers, lack of understanding about the needs and preferences of marginalised groups, and ineffective interventions all contribute to inadequate sexual and reproductive health and rights. LSHTM, and the ACCESS consortium, took a participatory approach, using the latest methodologies to work with partners and beneficiaries with the aim of developing and testing the effectiveness of a range of interventions, generating new evidence and making recommendations that will improve peopleŌĆÖs health and wellbeing

The ACCESS consortium was axed by the UK government without warning in April 2021, six months after the implementation phase began, as part of the UK aid budget cuts. Nevertheless, we produced some useful outputs.

ŌĆśGlobal GoodsŌĆÖ

We have developed ŌĆśGlobal GoodsŌĆÖ from this project, listed below.

You can read our publication on making authorship guidelines that promote equity in co-produced academic collaborations .

You can read our article Methods to measure effects of social accountability interventions in reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health programs: systematic review and critique in the Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition .

You can read our BMJ Opinion Blog on Covid-19 in humanitarian settings: addressing ethics to reduce moral distress .

You can read our article ŌĆśPreparing humanitarians to address ethical problemsŌĆÖ in Conflict and Health .

You can read our article on COVID-19 testing acceptability and uptake amongst the Rohingya and host community in Camp 21, Teknaf, Bangladesh in Conflict and Health .

You can read our article on making a graphic elicitation technique to represent patient rights in Conflict and Health .

You can read our commentary with WHO Community of Practice, ŌĆśUnpacking power dynamics in research and evaluation on social accountability for sexual and reproductive health and rightsŌĆÖ, .

You can read our protocol Protocol for ŌĆ£Sexual and reproductive health service considerations for people of diverse sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics (SOGIESC): a systematic reviewŌĆØ .

You can read our Lancet commentary Lancet publication ŌĆśCommunity participation is crucial in a pandemicŌĆÖ .

You can read our blog post, ŌĆśWho writes what? Responsible authorship recognition in co-produced researchŌĆÖ, at our LSHTM DEPTH website here (scroll to September 2021).

Check out previous DEPTH blog posts .

Our latest blog is by our former DEPTH Project Manager Laura Dix, who reflects on 18 months working with us in collaborative research at LSHTM. Laura offers a brilliant perspective that we donŌĆÖt always gain ourselves from the ŌĆśinsideŌĆÖ - here are her top 5 reflections on collaborationŌĆ”

Co-production. Co-creation. Expert-led. Service User Involvement. Patient Public Involvement.

Whatever you want to call it, in recent years collaboration and partnership with communities has become a more visible and debated practice in many different sectors, from global NGOs to local government to academia.

This shift is an important one. Who wouldnŌĆÖt argue that the people most affected by an issue should have a say not only on how it is defined, but what solutions are put in place? However, the language of ŌĆ£involvementŌĆØ has come to cover multiple different methods of engagement, ranging from truly equal partnerships to just a label slapped on a project to make it sound good.

I came from the charity sector in October 2020 to join the Team at , who are specialists in involving communities in research to promote health and equity. I was fascinated to find out how the experts ŌĆśdoŌĆÖ involvement, and what differences there might be in the jump from an NGO to academia. So after 18 months as a fly on the wall in my excellent team, what have I learned about co-production? Here are my top 5 reflectionsŌĆ”

1. It can be helpful to broaden your definition of community

We often talk about community involvement in terms of how we engage patients, service users or clients, but it can also be helpful to expand this definition of ŌĆ£communityŌĆØ and include within it others that are participating in the project - for example our colleagues, external stakeholders, consultants and co-researchers.

Once we see a project as having multiple communities of interest, it might be helpful to also use models of co-production to understand and take into account different levels of interest, involvement and input that various people want, or are able, to input on a project. This has the benefit of helping to build relationships and knowing who to engage with, and at what level that engagement happens. For example, many user involvement approaches show it as a sliding scale or as a ladder, such as this one from Passio:

Credit:

By using this model to categorise the involvement of everyone working on the project you can understand more about what sort of approach to take, meaning no assumptions are made and that everyone is able to speak about their needs on the project.

A great example is - a programme designed to support and engage marginalised populations in complex and challenging environments (e.g. scenarios where humanitarian aid is required such as post-earthquakes or in refugee crises) to claim and access comprehensive sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information and services. The DEPTH team were part of this consortium, which saw multiple people come together from various nations, sectors and forms of expertise. The consortium had many layers because it involved lots of different organisations and staff, from those with more strategic input to those deployed operationally in-country. Being part of the consortium and seeing these layers as different communities meant that each has different motivations, interest and opportunity to be involved. The consortium leads (IPPF) were brilliant at asking how people wanted to be involved - not assuming that everyone wanted or needed to be part of everything - and using this language to ensure the right people were in the right room at the right time. Being part of such a large ŌĆścogŌĆÖ in the consortium was also interesting because there were times when I noticed I wanted more of a consultation style role over an equal partnership and vice versa, based on how much time, interest and ability to input I had. Using a co-production model for this was helpful to understand where we fitted into the wider project, to clearly define roles and responsibilities, and also see where we had more or less influence.

2. ItŌĆÖs ALL about power

I came to academia from a domestic abuse charity, and lots of our conversations there were about power: power in an individual sense (e.g. an individualŌĆÖs power over another) but also about power in a more structural sense, relating in particular to sexism and inequality, and increasingly racism and ableism.

Being aware of the power you have on a project is key when thinking about service user involvement. Constant reflection on issues such as whose voices are privileged, who is making decisions, who is being heard the loudest, or what assumptions are being made is so important to ensure that your involvement is not simply replicating power structures in society but is actively working to challenge and/or dismantle them.

This is best described as the difference between ŌĆ£doing withŌĆØ over ŌĆ£doing toŌĆØ, as in the model below:

Credit:

But how do we find ways to talk about power and become aware of ways it is being used in our PPI?

One place conversations about power are happening is part of decolonisation work developing in academia. The DEPTH team discussed decolonisation across their work, challenging what is being taught to students and how this teaching represents the world. Lots of this work is about power - who has the power to tell stories and whose stories are heard. It is important to build in time to reflect on how involving people in projects can replicate problematic power structures and how to challenge them. Some people are critical of decolonialisation work and itŌĆÖs definitely not a panacea, but it offers a useful place to jump in to thinking about privilege and power for others.

3. Project managers can uphold problematic power structures

Project management is essentially creating a structure to get something done. We might think ŌĆ£weŌĆÖre just doing project management - what does racism, sexism, ableism and so on have to do with us?ŌĆØ But itŌĆÖs important to remember that structures arenŌĆÖt neutral: within the structures we create, the policies and processes we write, and the tasks we carry out, power and privilege exist. So even administrators, project managers and other support staff need to reflect on how the bureaucracy around a project could replicate or encourage oppression and marginalization of those involved in the research.

Often we donŌĆÖt think about how things like a project plan or a budget can have longer term ramifications on co-production. But these are exactly where we should be thinking about service user involvement! For example, if we are writing a budget we may not have built in money for travel for service users or childcare costs, which may block peopleŌĆÖs ability to participate. Or we may make our timeframes too tight to truly involve people, practicing tokenism rather than the time needed for co-production (see graphic below).

4. Find ways to make power more transparent

All sectors have specific problems relating to power. In academia, issues around authorship are some of the most prominent. Writing papers (authorship) is a huge part of the role and prestige of an academic. However, deciding who is first author on a paper (and the order of the authors names) is important, and credit for authorship can be an area where power obscures participation.

As part of their PPI guidelines, NIHR (a big research funder) encourage consultation, collaboration and co-production with research participants and offer frameworks of how to engage people to take on more ownership of the research. But how do you balance issues of power here and make it more transparent?

One way the team have made power more transparent is by creating These are a really useful guide to talking through these issues and establish who would like to collaborate, thereby shining a light on how power works and ensuring we are able to talk about it and negotiate a more equal and equitable partnership with co-authors, who may be research participants or experts from NGOs and may be unaware of some of the rules around authorship or discouraged from asking for due recognition.

5. The DEPTH Approach Works.

The ŌĆśDEPTH approachŌĆÖ is the teamsŌĆÖ formula to involvement within health research. And after seeing it in action, I can confirm it works! I witnessed the team working on our current project ŌĆ£Routes: new ways to talk about covid for better healthŌĆØ which has a focus on Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, and migrant workers in precarious jobs, and their experiences of Covid-19 and healthcare

The DEPTH approach includes a framework around how to galvanise communities to come together, share their experiences, analyse the results and co-produce recommendations for how healthcare could work better to centre their needs and priorities. The team developed an approach for how to involve those with lived experience on the team and as co-researchers (even in a project with such tight timelines), a series of insightful questions to ask during a mapping phase, and use their links and networks to reach out to a huge range of people. Involving communities is always complicated, but the DEPTH approach is a thoughtful and considered approach to how to co-produce health research which has been honed over many years of expertise within the team. The insightful results we are seeing and engagement by GRT and migrant worker communities within the project shows how successful this method is.

Conclusion

Participation at every level can be powerful, but the most important thing is to be transparent about what type of involvement people can expect - and its limits. This means people can give informed consent to take part in research as they truly know what they are signing up for, it shines a light on power (and where itŌĆÖs problematic), and it is best practice for working in partnership.

I started this work in the womenŌĆÖs sector, and came across the most domestic abuse who had created a ŌĆ£ladder of involvementŌĆØ to show how services can involve their clients. It seems only fitting that as I returned to their work as inspiration for this article, I realized that it was a student at LSHTM that helped create it all. How fitting that my two worlds have come together at the intersection of how we place people at the heart of their own care.

2021 was a busy year, for DEPTH and for researchers and communities worldwide. Here are some numbers that summarise our in-DEPTH work in2021...

1

New research project, Routes: new ways to talk about Covid for better health. Focus on Gypsy Roma and Traveller communities, and migrant workers in precarious jobs. This participatory research is funded by the NIHR Public Health . The project responds to the Health and Security Agency need for urgent information on barriers and opportunities for improving health services relating to COVID-19 community prevention and response. Check out our brand-new webpage for more information.

137

Number of organisations and individuals contacted as part of our Routes project work, across mapping conversations, interviews, dialogue sessions and stakeholder conversations.

3

Major funders for our participatory DEPTH research: UK Government FCDO (ACCESS: Approaches in Complex and Challenging Environments for Sustainable SRHR), NIHR (This Sickle Cell Life) and UK Government NIHR/DHSC (Routes: new ways to talk about Covid for better health. Focus on Gypsy Roma and Traveller communities, and migrant workers in precarious jobs). Across these projects, we are working in dialogue with communities as well as with policymakers, researchers and advocates.

14

Points in our preliminary guidelines for equitable academic authorship in collaborative health research. We built on good-practice guidelines from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (), the British Sociological Association () and Committee on Publication Ethics () to recognise the specific needs of authors in co-production contexts, including research conducted with non-academic collaborators. You can read our guidelines, for free, .

2

Finalist nominations for the &Us ŌĆśŌĆÖ. Dr Alicia Renedo and Dr Sam Miles were shortlisted for their work with children and young people, ŌĆśchampioning their voices to inspire students and health workers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical MedicineŌĆÖ. The nominations and shortlisting were run by young people. You can read more on our .

8

Talented research degree students undertaking doctorates with DEPTH staff: , Casey-Lynn Crow, Julia Fortier, Weiqi Han, Erin Hartman, Mary Mbuo, (recently completed) and Maritza Lara Villota.

1,278

Total number of followers of ourŌĆ»ŌĆ»and ourŌĆ»ŌĆ»Twitter accounts. Check out our feeds out ifŌĆ»youŌĆÖreŌĆ»not signed up for daily updates, news articles and research findings.

90

Number of days we had to wind up a huge consortium project. ACCESS (Approaches in Complex and Challenging Environments for Sustainable SRHR) was axed without warning by the government in spring 2021. We nevertheless developed exciting outputs to share from our consortium work, available here. You can also read a summary of the project from our partners at IPPF (International Planned Parenthood Federation), .

2

Strategy days to practice teamwork initiatives, discuss DEPTH priorities and plan our research strategy.

5

Total number of canine DEPTH team members. Gus and Ziggy are Sam and LauraŌĆÖs puppies, while Bertie, Colin and Pepa are honorary doggie members!

We hope you enjoyed reading our 'Year in 2021'. Watch this space for new developments in 2022...

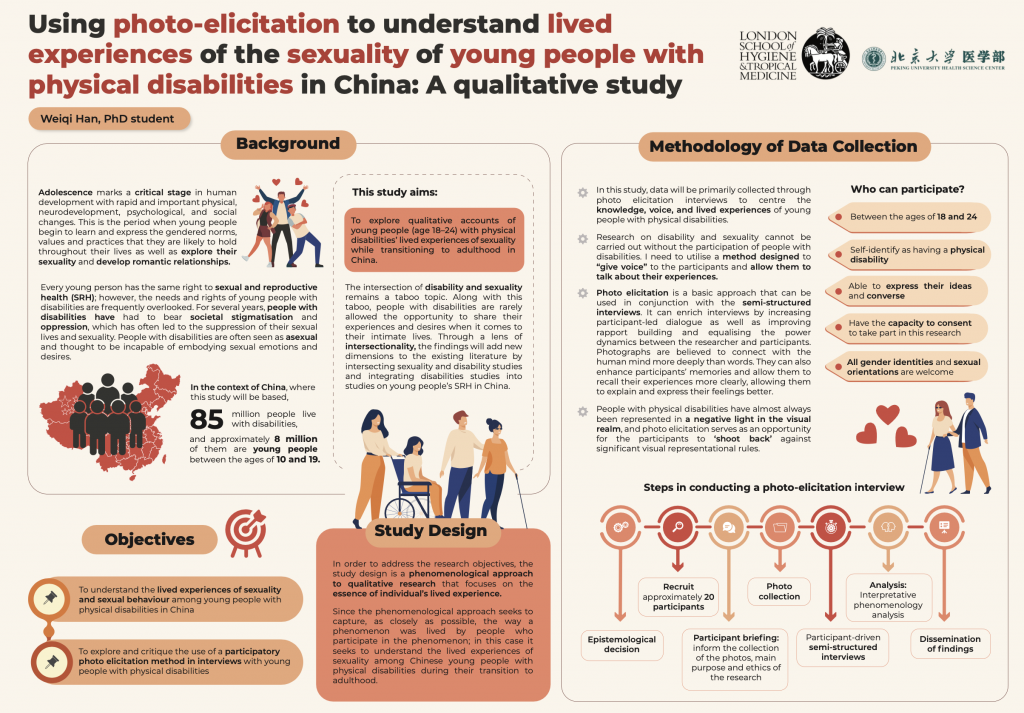

Our latest DEPTH blog comes from PhD researcher Weiqi Han, supervised by Professor Cicely Marston. Weiqi has just won best poster at the for her work on using photo-elicitation to understand the lived experiences of sexuality of young people with physical disabilities in China. Over to you, WeiqiŌĆ”

ŌĆśI really enjoyed my time at the 2021 Research Methods e-festival last month, hosted by the National Centre for Research Methods and methods@manchester. Around 80 sessions were held over five days, with more than 130 speakers offering diverse perspectives on the festivalŌĆÖs theme: innovation, adaptation and evolution of the social sciences. The e-festival was brought together by a common interest in interdisciplinary approaches within and across the various social sciences. It was web based and was highly interactive. Attendees could join sessions via live video streams, take part in community discussion boards and network with other scholars.

I was so excited to win best poster at the festival. Currently, I am in the qualitative data collection stage of my doctoral work. I am honoured and grateful for this recognition, and I hope that it draws more attention to studies on the intersection of sexuality and disability.

For many years, people with disabilities have encountered societal stigmatisation and oppression, which often causes them to suppress their sexual lives and sexuality. People with disabilities are often seen as asexual and thought to be incapable of embodying sexual emotions and desires. The transition from adolescence to adulthood is a time of instability, experimentation and exploration in various areas of life, most importantly in relation to sexuality. In the context of China, where this study will be based, 85 million people live with disabilities, and approximately 8 million of them are young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years. Everyone has a right to sexual and reproductive health, and young people with disabilities should not be denied this inalienable right simply because of their disability.

The study seeks to explore young people (age 18ŌĆō24) with physical disabilitiesŌĆÖ qualitative accounts of their lived experiences of sexuality while transitioning to adulthood in China. Accordingly, a phenomenological approach to qualitative research will be utilised that focusses on the essence of the individualsŌĆÖ lived experiences. Data will be primarily collected through photo elicitation interviews to centre the knowledge, voice, and lived experiences of young people with physical disabilities.

People with disabilities are rarely given the opportunity to share their experiences and desires about their sexuality and intimate lives. Research on disability and sexuality cannot be carried out without the participation of people with disabilities. People with physical disabilities have almost always been represented in a negative light in the visual realm. To enhance the participant-led understandings of experiences of sexuality and disability, I decided to utilise a method designed to ŌĆśgive a voiceŌĆÖ&▓į▓·▓§▒Ķ;to the participants and allow them to talk about their experiences. Specifically, I will use photo elicitation in conjunction with semi-structured interviews to gain a ŌĆśphenomenological senseŌĆÖ of the importance and meanings that the content of the photos holds for the participants while allowing them to relate and share their issues, experiences and concerns.ŌĆÖ

Thank you for your guest blog Weiqi, and we look forward to learning more about your project in this historically under-researched field. Watch this space!

You can contact Weiqi for more information on weiqi.han@lshtm.ac.uk.

DEPTH team members collating research themes

New term, new research! WeŌĆÖre very excited to publish our latest article: ŌĆśŌĆÖ, open access in Global Public Health. This piece brings together our thoughts on academic authorship from our recent project on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) for marginalised populations, with our thinking on knowledge co-production from the project ŌĆśThis Sickle Cell LifeŌĆÖ, a sociological study of young peopleŌĆÖs experiences of paediatric to adult healthcare transitions

The call for papers for a special issue of Global Public Health on ŌĆś(Re)imagining Research, Activism, and Rights at the Intersections of Sexuality, Health, and Social JusticeŌĆÖ offered us the perfect opportunity to crystallise some of the discussions we had and are still having as a research team about health co-production, academic research, authorship, and social justice. We take collaboration and engagement very seriously in here at , and felt that established authorship guidelines, while excellent benchmarks for ethical research and publication practices, arenŌĆÖt always fit for purpose when it comes to co-produced work with different stakeholders. As we reflect in our Discussion:

There are numerous structural barriers to full collaboration that have an impact on authorship. The structural barriers to collaboration in general can be revealed in decisions about authorship ŌĆō they are highlighted in who makes authorship decisions, and who benefits from them, and the structures and conventions that support and entrench inequities and devalue collaborative in favour of competitive working.

In light of these tricky contextual norms, we found numerous questions that needed unpacking: who is an author, and what do they contribute? When does a personŌĆÖs place in the acknowledgements change to place on the author list, and when should it? How might we think more deeply about academic products and knowledge so that we do not inadvertently help supress voices that are already less heard? These voices are often less heard in academia because of the structures and customs of the academic system, so what impediments can we sidestep while acknowledging we still function within that system?

The result of our discussions is the article, which starts to explore how we might more explicitly pursue recognition of co-produced contributions to academic research. One way to hold ourselves and each other to account in equitable ways of working is through authorship guidelines, which we hope will prove useful as a jumping-off point for others engaged in collaborative work ŌĆō especially with practitioners, activists, or non-academics, whose contributions and knowledges donŌĆÖt always fit neatly into academic ŌĆśboxesŌĆÖ. Having reflected on who tends to be disadvantaged by the current systems, we suggest that spending time thinking critically (and sometimes painfully) about these positions and relations can help to scaffold authorship norms that are fairer and more transparent.

You can read the whole piece , free and open-access. But in this blog I wanted to highlight our authorship guidelines specifically. They are amended from existing excellent offerings of ICMJE and BSA, and move beyond them in that here we incorporate more explicit attention to different stakeholder contributions, and also to co-produced outputs. These are both themes that are long overdue more sustained reflection, and in an academic context of ever-increasing cross-disciplinary and cross-country collaboration and co-production with communities, we hope they prove useful for other researchers out there.

Take a look at our suggested authorship guidelines and see what you think ŌĆō and reply to this post if you have suggestions for improvements or any other comments:

- The nature of academic publication processes and authorship conventions should be explained to all partners so that the meaning of authorship and involvement is clear to all parties regardless of university affiliation or discipline.

- The project research/writing team should list details of expected papers early in any sub-project, including expected authorship and author order (especially first author).

- The rationale for authorship and author order should be transparent. All authors must make a substantive contribution to the intellectual content of the publication.

- Non-academic project partners should be invited to co-author the work, with plans in place early on about how to handle suitable contributions. Level of input required must be discussed and agreed early on to ensure clarity on how authorship is allocated.

- Contributors whose contribution does not in the final product meet the criteria for authorship should be named in the acknowledgements. Named individuals must be informed so that they can withdraw their name if they wish.

- Where used, translators/interpreters must be named in the acknowledgements.

- Lead author must draft the paper, with input from other authors, and be responsible for submitting the paper and making any revisions in response to referee comments. The lead author must not submit any paper without the agreement of the named authors.

- All academic publications should contain a statement about the contribution of each named author.

- The PI must approve submission of academic articles from the project and must be named as author if criteria for authorship are met.

- Academic journal publication must be supplemented with publication of findings in other channels to ensure inclusive dissemination (e.g. tweets, policy document, media article, public workshop).

- The particular needs of members of the team should be considered in arranging publication strategy (e.g. need to gain experience of lead authorship). However, any named author must fulfil the requirements for their authorship position.

- Sole authorship will not generally be possible or desirable within the project because of the collaborative nature of the work and our recognition that knowledge is co-produced through these collaborative relationships.

- Consider adding the consortium or project name to all work with numerous contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship and listing key contributors to the paper in the acknowledgements.

- In the event of any disagreements or confusion about authorship or author order, please refer to these guidelines within the writing team. If there is still confusion, please request assistance from the PI as the question may need to be referred for a wider discussion and/or the guidelines may need to be clarified.

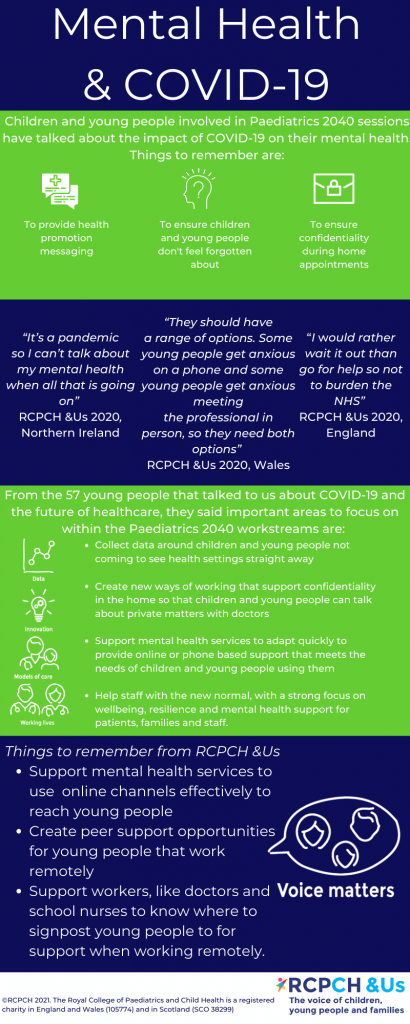

In uncertain times, it was a real morale boost to receive some good news from (RCPCH). The RCPCH team, who advocate for and involve children, young people and families in health services, recently told us that DEPTH researchers Dr Alicia Renedo and Dr Sam Miles from were nominated for the RCPCH & Us Voice Champion Award.

The is a youth-led award recognising adults that go over and above their job role to work with RCPCH &Us to improve services with children, young people and families. The nominations were all anonymised and reviewed by young people from RCPCH &Us, who created criteria and a scoring system, then worked virtually together to review and discuss the fantastic nominations.

Alicia and Sam were not only thrilled to be nominated but also impressed by the youth-led nature of the nomination and award process. Putting young people at the heart of health services participation is key to how we work in DEPTH, so the RCPCH & Us Voice Champion Award feels like a real reflection of the values that we prioritise in DEPTH, too.

This Sickle Cell Life is an NIHR-funded research project that explores the voices and experiences of young people with sickle cell as they transition from paediatric to adulthood, and adult healthcare services.

Project Research Lead, Dr Renedo, says of the nomination:

ŌĆ£This was excellent news for the DEPTH team. We admire the work done by RCPCH &US, and they are a role model for participation, so coming from them, this nomination felt very special.ŌĆØ

Project Principal Investigator and DEPTH Group Director Prof Cicely Marston said:

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm so delighted to see Alicia and Sam recognised in this way. They work really hard to make sure our participatory work is inclusive and their work with young people on this project has been brilliant.ŌĆØ

We feel very honoured to be nominated, and thank all of our collaborators and colleagues for their role in making This Sickle Cell Life happen. You can read an ŌĆśEvidenceŌĆÖ brief of This Sickle Cell Life by NIHR .

Some of the This Sickle Cell Life collaborators (Top row L-R: Patrick Ojeer, Ganesh Sathyamoorthy, Sam Miles, Nordia Willis, Alicia Renedo, Andrea Leigh. Bottom row L-R: Cicely Marston, John James, Siann Millanaise. Photo: Anne Koerber)

Continuing from of our Q&A last month, hereŌĆÖs Part 2 of our Q&A with Emma Sparrow from at .

This interview focuses on working with young people in a tricky year when it comes to participation. We asked Emma how RCPCH &Us have managed to carry on with engagement activities since CovidŌĆ”

Adapting and engaging in a pandemic

Emma: We had to look at all of our projects and decide which ones are appropriate to carry on, because we had some that were about very sensitive topics that in-person would have been challenging, and would have needed a lot of support and aftercare ŌĆō for example complex respiratory illnesses. We looked at those and thought, you know, what, thereŌĆÖs a pandemic going on, which includes respiratory illness, nowŌĆÖs not the time to be phoning people up or talking to them and saying, ŌĆśwhat do you think about this?ŌĆÖ and ŌĆśwhat you think about that?ŌĆÖ First we did a wellbeing assessment on our workstreams and agreed which ones we were going to park for a bit, based on a welfare context. Then we spoke about what the missing gap in provision might be, because everybody is going to suddenly do everything the same and we donŌĆÖt want to duplicate. We actually didnŌĆÖt go as quickly as some of the other organisations to put out loads of new children and young people-focused information about COVID. What we did was pull together existing information on COVID and put it into a place that was easy and clear for families, parents and children and young people to see.

We wanted to give children and young people a meaningful role and we had to be creative

One of the things that we wanted to do was give children and young people a meaningful role. We asked: what are the gaps? Something that came up from paediatricians was that they were really worried that children and young people wouldnŌĆÖt be going to their regular appointments anymore, so could we create a for them? So we did, and thatŌĆÖs still getting downloaded now, which is really cool. ItŌĆÖs something a bit more creative for them to write down their questions or things that have happened that are good. A doctor came to us and said ŌĆśwe want to thank our children and young people for taking part in the covid effort and not coming in and not playing outside, so can you create an ?ŌĆÖ So we created e-cards for thank you and birthdays, and last month 5,000 of those were viewed.

We picked up on childrenŌĆÖs and young peopleŌĆÖs concerns

As time went on we worked with lots of other groups, virtually. Lots of Teams, Zooms, and all that kind of stuff, to find out: whatŌĆÖs happened for you with health during COVID? What are your appointments like and what are you missing? WhatŌĆÖs the information like? We picked up concerns from children and young people about the fact that COVID information wasnŌĆÖt targeted at them. It was for adults. It also wasnŌĆÖt giving a positive message about children and young people, so they were seen as the problem rather than part of the solution. There were also significant gaps forming around mental health support. That led us into a couple of new projects focused on COVID, but specifically from children and young peopleŌĆÖs points of view. One was about , where we wanted to children and young people to tell us where theyŌĆÖre getting their mental health support and where are the gaps. Another one is working with young people to try and get a press conference for young people, because theyŌĆÖre not allowed to ask questions at the government press conferences, you have to be over 18 ŌĆō excluding a whole group from having their questions heard or having a role. So weŌĆÖve been working with other charities to call for a press conference to answer questions from children and young people.

We got young people involved in reviewing evidence on patient experience of COVID

Finally, we realised that there were thousands of studies being done on COVID. The RCPCH had clinicians coming together to review which studies were being published on children and COVID, which got me thinking that actually there was also thousands of studies being published of what young people had said. Lots of charities were asking their children and young people about the impact of the pandemic, and then publishing the results. And we just wanted to give young people a chance to also do what the adults are doing: so if doctors can review scientific journals about COVID, young people can review a patient experience of COVID. We pulled together a group of a small group of young people and over 12 weeks, invited them to look at about 20 different published studies of around 60,000 children and young peopleŌĆÖs voices, say, from cancer patients, mental health experiences of young people, children and young people or young carers, across the UK.

And they did what we do in our world ŌĆō they conducted some thematic analysis, they explored the key trends, they developed them, they then created eight different topics that came up, and they slotted in the data, with a ŌĆśforŌĆÖ and ŌĆśagainstŌĆÖ for each topic. Topics included things like mental health and family dynamics, employment, education. They wanted to make it make a difference to the NHS, and the NHS at the moment are writing recovery plans on how to how to restart the NHS. So theyŌĆÖve boiled all of that work down and they volunteered over 100 hours doing this project over about three and a half months. TheyŌĆÖve turned the three priorities they have developed for the NHS into posters. The posters include the priority, the problem, the solution, the impact, a quote and some stats. Since launching, the recovery plan priorities have had about 28,000 Twitter impressions. You can read more about the findings online.

The work has elevated the voice of children and young people ŌĆō and made people understand they have a lot to say

Emma: We also hosted a debate with doctors about whether paediatricians should be thinking holistically or medically during COVID, because for children and young people, itŌĆÖs about their mental health as well. That project just feels so different from what weŌĆÖve done before. We had to really think through safeguarding and wellbeing, so we didnŌĆÖt overwhelm the young people who led it. This project very much felt like we were actually paralleling something that was going on in the academic part of the college, and doing the exact same thing, but for children and young people, which felt very different. It has elevated children and young peopleŌĆÖs ability, both in the college and in the sector. And itŌĆÖs really made people understand that they have got a lot to say, and they understand whatŌĆÖs going on, and have a lot to offer.

So on the whole, weŌĆÖve managed to find a way or find a tool or find an approach that makes it fun and entertaining and interesting and focused on them rather than the topic sometimes.

The good thing about having to change our work is that weŌĆÖve been more connected to RCPCH wider internal projects. The benefit of voice has been seen in a different way. And for us, we had to take that opportunity and run with it ŌĆō weŌĆÖve had 200 new children and young people involved during the COVID pandemic, who have between them completed over 330 hours of volunteering.

Voices are being heard and the professionals are engaging more

Emma: We give advice to people that are starting out on a project or want to talk about PPI [patient & public involvement] and IŌĆÖve had so many more requests over the last three months for people that want that advice. And I think itŌĆÖs because children and young peopleŌĆÖs voice is now seen differently. TheyŌĆÖre really seen as being integral. ThereŌĆÖs so much further we could go, thereŌĆÖs a million other things we could be doing that are even more innovative and creative, and increasing their reach, but youŌĆÖve got to start somewhere.

Barriers to participation ŌĆō too much time online but also digital exclusion

Emma: ThereŌĆÖs different barriers and challenges according to which audience youŌĆÖre coming from. For children and young people, one of the challenges that theyŌĆÖve said to us is that itŌĆÖs really overwhelming that everything is online. WeŌĆÖve really got to understand that because whilst we think weŌĆÖre doing something fun and exciting, and itŌĆÖs online for an hour, theyŌĆÖve already had school online, for some of them health appointments online, mental health appointments, and counseling online. TheyŌĆÖve had zoom calls with friends and family, theyŌĆÖve tried to keep fit online. And then weŌĆÖre coming at them with another online thing. Another challenge for them might be: maybe I havenŌĆÖt got somewhere confidential and private to do online stuff where people arenŌĆÖt listening in. Or maybe I havenŌĆÖt got a good device. So weŌĆÖve really looked at the challenge and been as inclusive as possible. You can join our online sessions on phone, you can do it on WhatsApp, you can join via video, you can have no video. You can use the chat, or you donŌĆÖt have to use the chat, you can do it by email if thatŌĆÖs better ŌĆō itŌĆÖs all your choice. For us itŌĆÖs a challenge because weŌĆÖre having to run four or five different tech options for a one-hour session. But itŌĆÖs about understanding that not all children and young people want to be on video, not all children and young people have got a device that lets them Zoom. Maybe all theyŌĆÖve got is a landline, which means they can phone in.

The challenge for participation and engagement is donŌĆÖt get complacent and think that your games and activities can all work with everyone seeing everything, because they canŌĆÖt. ItŌĆÖs about inclusion. And that comes from children and young people saying: I might be sharing my laptop with five other people in my house, so I canŌĆÖt use Teams at the same time, but I will phone in because IŌĆÖve got a mobile. WeŌĆÖve had to really think it through. Another challenge is always remembering whatever youŌĆÖre talking to children and young people about might be overheard. So donŌĆÖt put them in positions that makes them disclose stuff that actually might not work well in their family environment. WeŌĆÖve worked hard to create safe spaces, and to work with each group that weŌĆÖre talking to, to make sure we understand what their space is like at that moment. Because you canŌĆÖt start a conversation about money and poverty, when their parents are listening and they might feel that theyŌĆÖre being judged or that the young person feels like theyŌĆÖre judging their parents or living environment.

How can we make it fun? How can we make it inclusive?

Another challenge has been how we can make it feel fun. If youŌĆÖre using devices for presentations, or for school, we donŌĆÖt want to be like school on your computer. In the back of our heads weŌĆÖre always thinking letŌĆÖs not overwhelm our children and young people, they donŌĆÖt have to come to the project if stuffŌĆÖs going on. So weŌĆÖve really been conscious about trying to understand what people might be going through. And then to think about things like donŌĆÖt drink or eat when youŌĆÖre on camera, because not everyone has got enough food in their house. You would do that in the meeting room, but if we were in the meeting room, we would have given them food and drink. Whereas for us on camera, weŌĆÖre being really careful about stuff like that. So I think that thereŌĆÖs some challenges. The one that weŌĆÖre looking at now is where we would normally do community outreach to reach people who arenŌĆÖt connected to any projects. That will be a challenge and we need to think about how best to reach out to that cohort. But no challenge means that itŌĆÖs the end and weŌĆÖre not there yet! It just means that I need to think harder about how IŌĆÖm going to get past it.

I knew the COVID studies review would give young people a platform that theyŌĆÖve never had before. But how can you possibly do that safely? If I was in the room, IŌĆÖm able to see their visual cues, IŌĆÖm able to unpack things over lunch, IŌĆÖm able to stop the session and do something entirely different. I spoke to a friend whoŌĆÖs a youth worker and she said: ask the young people, theyŌĆÖll tell you what works for them, so we did, and they knew all the answers and helped shape the project throughout. In the end they decided that we couldnŌĆÖt do all of the studies. We found 33 but they said that they could only manage a certain number but thatŌĆÖs cool. At every stage I just kept checking in with them. They will tell us what works for them. ItŌĆÖs co production even in that sense.

What tools can we use for remote working with children and young people?

The first thing I would have to say for anyone about to do is go and talk to your information governance manager. Because whatever you think might be able to be used might not be able to be used for lots of different reasons. One thing we used is , because the young people said for the COVID studies review they wanted somewhere where they could collaborate on documents, but we canŌĆÖt use Google Docs because of a GDPR issue. IŌĆÖve never used anything like that before with young people. ItŌĆÖs so good. They could ask questions and comment on each otherŌĆÖs documents. But they could also see really clearly what was happening at what stage and what they could add to if they had a bit more time. IŌĆÖve been trying to find a voting app online, because that is key to so many of our projects, to be able to anonymously prioritise five or six different things. And allows you to do that. You donŌĆÖt have to put any personal data in, you just get given a code. And then theyŌĆÖve got lots of different voting tools that you can use. Having a virtual whiteboard is really important as well, like . But going back to inclusivity, if weŌĆÖre using JamBoard, and IŌĆÖve got two people that phoned in, I will take a screen grab of it and then WhatsApp it to them so they can see it building. And itŌĆÖs keeping that in mind as well, to make sure that youŌĆÖre not inadvertently excluding someone because they havenŌĆÖt got the same software in front of them.

Overall, I think we keep adapting, learning and changing to the meet the needs of children and young people engaging with us through the pandemic, as we learn new digital tools or approaches and learn from the group. ItŌĆÖs been an opportunity to really relearn everything you have always done and to reflect, update and adapt which has been hard at times but so rewarding when you see the outputs and outcomes.

Attendees at the participatory dissemination event for This Sickle Cell Life with DEPTH at LSHTM and RCPCHŌĆÖs &Us (Photo: Anne Koerber)

Contacts

To find out more about the RCPCH &Us programme or to access their free resources and support go to or contact and_us@rcpch.ac.uk, and follow them on twitter @RCPCH_and_Us.

You can read about the RCPCH & Us collaboration with LSHTM on ŌĆśThis Sickle Cell LifeŌĆÖ&▓į▓·▓§▒Ķ;here.

We were very excited to meet with Emma Sparrow from . Read on for Part 1 of 2 blog posts that cover all things engagement, involvement, and PPIŌĆ”

We began by asking Emma to explain her role, and how she and her team approach child health and engagement.

Part 1: How do we engage with children and young people and amplify their voices?

Improving child health is more than just paediatrics

Emma: The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health () is a charity, but as a Medical Royal College, it helps to support the specialism of Paediatrics. WeŌĆÖre slightly different to other Royal Colleges because we are the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, rather than the Royal College of paediatricians. So it means we can get involved in the whole child health agenda, which is obviously much bigger than just paediatrics. The me is the network for children, young people and families to help inform and influence all of the work of the College. It gives them a place to have their voice and space to say whatŌĆÖs going on for them and what could be done to improve child health services. Our approach is to get them involved in that ŌĆō itŌĆÖs not just somewhere to chat, itŌĆÖs somewhere to actually get involved in and progress social action. For us itŌĆÖs like a network approach where we try to get as many children and young people and families involved across the whole of the UK at all ages. This year, our youngest person involved is aged four, and we go up to age 25.

We focus on children and young peopleŌĆÖs voice and having them involved as volunteers or project members or giving views, but we also recognise that sometimes we will need to involve their advocates as well, whether thatŌĆÖs parents or carers. So we do ad-hoc work with parents and carers, but our primary focus is making sure that children and young people can get involved in the work the college is doing. We also ask what might be some of the challenges in child health, that theyŌĆÖre keen to explore and do something about with us?

People ask what children and young people think about somethingŌĆ” We turn the questions into games and activities and take them out on the road

Emma: Our approach is a bit different to most places. At RCPCH &Us, we work in three different workstreams. One is our roadshows and consultations. We get questions from loads of different people about what do children and young people think about something ŌĆō for example at the moment IŌĆÖve got questions on what do young people think about virtual health appointments, and what do children young people think about mental health experiences? What do children and young people think about how their data is used? ThereŌĆÖs lots of different questions that come into us. WeŌĆÖll turn these questions into a set of games and activities and take them out on the road, so that we can go and speak to as many children and young people as possible in as many different areas as possible, with as many different experiences as possible. ItŌĆÖs about us being out there with them, rather than expecting them to fill out a survey or a questionnaire or attend something with people that they donŌĆÖt know. Our roadshows might operate through schools or youth centers or playgroups or outreach. Or we might speak to children in care groups and carers, or speak to children and young people who are patients: weŌĆÖll speak to them outside their outpatient appointments, when they wait to see their clinician, or they might be inpatients.

We bring young people together for day-long ŌĆśchallengesŌĆÖ or for long-term projects

The next approach is challenges. These are ŌĆśtastersŌĆÖ, because children and young people donŌĆÖt necessarily want to sign away their lives to a project for three years, they might want to just see what itŌĆÖs like. WeŌĆÖll bring them together for a project day, where theyŌĆÖll come in not really knowing that much, and then learn all about a topic, they work with data, and come up with solutions and then present it at the end of the day. This is a bit like the project that we did with you at LSHTM last year ŌĆō This Sickle Cell Life.

The final approach for us is long term projects focusing on a specific area, with children and young people signing up to join that project team.

Developing workshops in the participatory dissemination event for This Sickle Cell Life (Photo: Anne Koerber)

Children and young people can participate in a way that works for them

Across our approaches, you could be a young person or child that just wants to tell us something in a conversation, thatŌĆÖs perfect. Or maybe you want to try something you want to do a challenge or maybe you want to do a project, but you donŌĆÖt need to do all three; children and young people can come in and out as it fits for them. We really want to make it an opportunity for them that they feel is meaningful, and that fits their life rather than fits my nine-to-five work life. It includes lots of weekends and evenings, and lots of doing things in lots of different ways. But for us, thatŌĆÖs important because it means that we get more children and young people involved who might not have been involved before, across different ages and backgrounds.

The other bit that is different is the way that we approach diversity. So we also make sure that any project weŌĆÖre doing has children and people from three different groups. One is universal, so theyŌĆÖre all just children or young people, because thatŌĆÖs who they are. Then we have a group where theyŌĆÖve got specific experiences that might change the dynamic for them, for example theyŌĆÖre young carers, or theyŌĆÖre Gypsy travelers, or something that binds them together with an identity. The third group is specialists, who have the health condition, for example asthma. That explains the way that we try to deliver our work by bringing together all three groups to have a full set of views, ideas and experiences.

How do adults respond to your approach, and the way you centre children and young people?

YouŌĆÖve always got people that are your allies and theyŌĆÖre brilliant for amplifying whatŌĆÖs going on. You can send them something and explain it to them and you know theyŌĆÖre going to get it straightaway and get it out. And then youŌĆÖve got the middle group who know that itŌĆÖs important, but maybe feel stretched ŌĆō overwhelmed by their work or their role. But when you can engage them in a conversation with an adult, or an organisation or a particular group of people you can see that they get it and they want to do more, but maybe the time is just not right. Those ones stay in touch, and they will get there. Then you have the people that just donŌĆÖt get it at all. Either they fundamentally donŌĆÖt want to get it, because they donŌĆÖt think it should be happening ŌĆō youŌĆÖll have people saying, ŌĆśbut why, itŌĆÖs not [children and young peopleŌĆÖs] role to say that we know what weŌĆÖre doingŌĆÖ. Or they donŌĆÖt get it because actually theyŌĆÖre at a point of crisis themselves, maybe in their role or their organization where itŌĆÖs entirely the wrong time.

We just have to really understand that weŌĆÖre going to have all of those groups, and theyŌĆÖre all important. They all have a role to play in what weŌĆÖre doing, but the way we approach them will need to be different. So the information we give to allies and the people that ŌĆśgetŌĆÖ it is what children and young people have said, and can you do something with it? Yes. The middle group, we see how we can show them the benefits of what children and young people are saying and then how it will actually support their work. For the ones that fundamentally donŌĆÖt get it, we tend to talk about the legislation: thereŌĆÖs a statutory duty to do this, it isnŌĆÖt something that IŌĆÖve just made up. ItŌĆÖs really important when you do engagement work that youŌĆÖre aware that everybody has a different motivation as to how it will land with them, and why they might be interested. But you can learn from them and work to give them what they need. Sometimes itŌĆÖs challenging but I just see it as an opportunity to share information in a different way. I have to just try harder to make sure that that it meets what they need.

I think you have to be an eternal optimist in engagement work, because everyoneŌĆÖs different, everyone learns in a different way, everyone participates in a different way. ItŌĆÖs all part of a process.

Attendees at the participatory dissemination event for This Sickle Cell Life (Photo: Anne Koerber)

Thanks for your time Emma. Look out for Part 2 of this Q&A next month!

Contacts

To find out more about the RCPCH &Us programme or to access their free resources and support go to or contact and_us@rcpch.ac.uk and follow them on Twitter @RCPCH_and_Us.

You can read about the RCPCH & Us collaboration with LSHTM on ŌĆśThis Sickle Cell LifeŌĆÖ&▓į▓·▓§▒Ķ;here.

Here are some numbers that summarise our in-DEPTH work for 2020ŌĆ”

The number of partner organisations in our UK Aid-funded We are excited to collaborate with , , , the , & .

The new research partners within the SRHR (sexual and reproductive health and rights) consortium. We are looking forward to working with colleagues at and , Nepal.

The number of citations of our piece in , Community participation is crucial in a pandemic. In it, we lay out steps governments and health bodies must take to ensure citizen participation.

The number of words in our final NIHR report, . You can learn more about the findings from our project here.

The number of sickle cell patient and carer experts with whom we co-produced This Sickle Cell Life. We recently collaborated with them to present study findings to London NHS Trusts.

The number of new followers to our and our Twitter accounts. Check them out if youŌĆÖre not signed up for daily updates, news articles and research findings.

The number of hits on our tweets in 2020 from our . If you donŌĆÖt follow us already, nowŌĆÖs your chance!

The number of links to other articles, profiles and research findings we included in our 2020. Our team wrote about all sorts of topics, from to the options for .

Photo by on

New year, new blog post! For our latest piece, researcher Dr Sam Miles reflects on the journey from PhD to first academic job, and offers some advice to ECRs (early-career researchers) pursuing careers in academia. This blog has been adapted from The &▓į▓·▓§▒Ķ;ŌĆśŌĆś Series, which you can find .

I was recently invited to write a guest blog for the about my journey to my first academic job. I donŌĆÖt have all the answers ŌĆō in the piece below I reflect on exactly why this might be, and my concerns probably resonate with many of you ŌĆō but I do have some ideas. Many of these came about after discussions with former students, current colleagues and other early-career researchers (ECRs) in the field, and notes of my own taken over the years.

ItŌĆÖs not as simple as a tick-list, though I cannot tell you how much I wish it were. I just hope that these ideas can be helpful to social science students here at and in the wider job market applying for postdoctoral or lecturer posts. I was asked to write the kind of blog post I wish IŌĆÖd read when I was starting to job hunt; with that in mind, here goes.

ItŌĆÖs one of those truisms that finding an academic job is hard. And it really is ŌĆō it feels somehow unlike finding any other kind of job, and the specific knowledge around academic job hiring processes is something youŌĆÖre also somehow expected to know, maybe by osmosis. ItŌĆÖs no wonder strikes so many of us. Take for example academic CVs, where longer is better. It goes against every fibre of my being to go over the 2 pages I was always told is the maximum you should fill. Even the listing of education/jobs/experience is differently ordered in an academic CV to CVs in every other job in the world. Job adverts themselves can be confusing in terms of terminology and contract type, or arcane or unclear working conditions, or freighted with acronyms without explanations. On top of this, salary, contract length and expectations of entry-level posts can be vague, missing or intimidating.

It all results in a task that feels unclear and applications that can feel rather uncertain. Usually, thatŌĆÖs through no fault of your own (as evidenced when youŌĆÖre several applications in, facing radio silence from each institution. Are you even doing it right?) Obviously, the offer of an actual job would answer that question, but academic posts are so competitive that your empty inbox may be more of a testament to a stricken job market than your own application ŌĆō and the has made a precarious market even worse. You will often be rejected without any feedback from the hiring institution. The standard response to requests for feedback is that feedback is only feasible at shortlist stage, but it is invariably difficulty to get to shortlist and interview if you donŌĆÖt gain feedback on what you need to finesse! In the absence of clear direction from institutions, you may need to utilise a few different approaches. IŌĆÖll lay out some that I used.

HereŌĆÖs what my own journey looked like: In the final year of my PhD, I applied to several lectureships. The applications I submitted were for posts that normally required a PhD, completed or near-completion. I took this to mean that they were open to nearly-there or newly-minted PhDs as much as anyone else, but have since recognised that the field of candidates is routinely so huge that many will have progressed a long way beyond this milestone. From asking more established colleagues at my institution, talking with early-career-researchers at a conference that spring, and looking out for the hiring announcements of successful candidates (people increasingly share job successes on Twitter), I realised the reality was that new PhD finishers rarely get these jobs. The market is crowded with brilliant and highly-qualified candidates. Vacancies are limited (and by , dwindling further).

It is now much more common for PhD finishers to work on one or several assistantships or postdoctoral posts before lectureships become a possibility. Even then, that post is often fixed term.

Photo by on

During my own job hunt, a Research Fellow post at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) caught my eye. It required a PhD in public health or related discipline, including social sciences. Alongside my own research covering some (but certainty not all) elements of sexual health via a, I made sure I researched reproductive health, which was the other component of the post and an area where I was less experienced. The specification emphasised qualitative methods, which matched my experience, and co-produced research outcomes with communities. My doctoral research was participant-centred and I had been reflecting on , but I wanted to develop this more in future work. The LSHTM post would specifically engage participatory research, so I took my knowledge of participatory action research (PAR) from my own work and brought myself up to speed on co-production and PPI (patient/public involvement) in health.